![]()

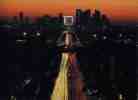

From the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel in the courtyard between the open arms of the Louvre, there extends one of the most remarkable perspectives extant in many modern city. It is called--though not in everyday speech--the Triumphal Way. From the middle of the Carrousel Arch, the line of sight runs the length of the Tuileries Garden, lines up on the obelisk in the Place de la Concorde, and goes up the Champs-Elysées to the centre of the Arch of Triumph.

The Louvres modest triumphal arch stands in the open space where customed nobles performed in an equestrian display--un carrousel--to celebrate the Dauphins birth in 1662. The design of the arch, an affable imitation of that of the Arch of Septimius Severus (Rome), was confected in 1808 by Percier and Fontaine, who also perpetrated a great deal of the Empire styles sphinx-fraught furniture and decoration. Napoleon, a record of whose victories in incised on the archs flanks, decorated the summit with the famed four bronze horses from St. Marks in conquered Venice. The Venetians had taken them from conquered Constantinople, which had acquired them in Rome, which, in turn, had looted them from, it is believed, the Temple of the Sun in Corinth. After Napoleons defeat, France was forced to return them--to Venice.

The Tuileries Garden, which fronted the Tuileries Palace (looted

and burned in 1871 during the Commune), has not altered much

since André Le Nôtre laid it out in 1664. Le Nôtre, who was

born and who died right in the garden, in the gardeners cottage,

carried the line of his central allée beyond the garden and out into

the country by tracing a path straight along the wooded hill west

of the palace. On this hilltop, 170 years later, the Arch of

Triumph was erected.

The Tuileries Garden, which fronted the Tuileries Palace (looted

and burned in 1871 during the Commune), has not altered much

since André Le Nôtre laid it out in 1664. Le Nôtre, who was

born and who died right in the garden, in the gardeners cottage,

carried the line of his central allée beyond the garden and out into

the country by tracing a path straight along the wooded hill west

of the palace. On this hilltop, 170 years later, the Arch of

Triumph was erected.

At the western edge of the garden, Napoleon III erected a hothouse, the Orangerie, and a court for real (or royal or court) tennis, the Jeu de Paume. The former is used for temporary art shows, the latter houses the Louvre collection of paintings by the Impressionists and their forerunners. Among the artists represented are: Cézanne, Degas, Gauguin, Manet, Monet, Renoir, Rousseau (le douanier), Toulouse-Lautrec, van Gogh. From the terraces on which these museums stand there are splendid views of the olympian traffic jams of the Place de la Concorde.

The formal exit gate from the Tuileries is flanked by two winged horses (17th century), and the entrance to the Champs-Elysées across the square is similarly garnished (horses, earthbound, 18th century), both pairs having been removed in turn from the water trough at Chateau de Marly.

The Place de la Concorde was designed as a moat-skirted

octagon in 1755 by Jacques Ange Gabriel. He had won

competition set by the échevins of Paris for a king-flattering

Place Louis XV. The river end was left open, and on the inland

side; two matching buildings were planned. The ground floor

was arcaded and the facade was nimbly adapted from the Louvre

colonnade, all with a refinement typical of the era. Although

Gabriel built eight giant pedestals around the periphery of his

place, they remained untenanted until Louis-Philippe gave them

statues representing provincial capitals going clockwise from the

Navy Ministry (Ministère de la Marine): Lille, Strasbourg, Lyon,

Marseille, Bordeaux, Nantes, Brest and Rouen. Louis-Philippe

also had the Luxor Obelisk, a gift from Egypt, installed in the

centre and flanked by two fountains. Later, the surrounding moat

was filled in, and the Place de la Concorde took on its present

geography.

The Place de la Concorde was designed as a moat-skirted

octagon in 1755 by Jacques Ange Gabriel. He had won

competition set by the échevins of Paris for a king-flattering

Place Louis XV. The river end was left open, and on the inland

side; two matching buildings were planned. The ground floor

was arcaded and the facade was nimbly adapted from the Louvre

colonnade, all with a refinement typical of the era. Although

Gabriel built eight giant pedestals around the periphery of his

place, they remained untenanted until Louis-Philippe gave them

statues representing provincial capitals going clockwise from the

Navy Ministry (Ministère de la Marine): Lille, Strasbourg, Lyon,

Marseille, Bordeaux, Nantes, Brest and Rouen. Louis-Philippe

also had the Luxor Obelisk, a gift from Egypt, installed in the

centre and flanked by two fountains. Later, the surrounding moat

was filled in, and the Place de la Concorde took on its present

geography.

Louis XVI was decapitated near the statue of Brest, January 21, 1793. The guillotine was brought back to the place four months later and erected near the gates of the Tuileries, and the executions went on for nearly three years, with a total of 1,343 deaths on this spot. An approximately equal number of persons perished in other parts of town.

Between the twin buildings the broad rue Royale mounts to the Church of La Madeleine, a stern oblong, fenced with columns 20 metres high, ostensibly a Greek temple but closer to the Roman notion of Greek. From 1764 to 1806 three false starts were made on building a church on this site. Napoleon ordered Vignon to build a temple to the glory of the Grande Armée but then vanished from the scene, and La Madeleine was not consecrated until 1842.

The Place de la Madeleine is the western terminus of the Grands Boulevards, which imitate the arch of the river from there north and east to the Place de la République and the Bastille. The glittering chic of the Grands Boulevards, which flavoured Paris life from 1750 to the 1880s, is gone with the boulevardiers, gone with Café Tortoni, the Café Riche, the Maison Dorée. The state-run Opéra Comique persists just off the boulevards des Italiens, the wax museum is still there on the boulevard Montmartre, and, a few doors away, Offenbach's theatre, the Théâtre des Variétés, still operates. The Théâtre de la Renaissance, where Coquelin created Cyrano de Bergerac in 1897, still functions on the boulevard Saint-Martin, as does the Théâtre de l'Ambigu, where Fréderic Lemaître, idol of boulevard melodrama, thrilled all Paris in the mid-19th century. Some of the movie palaces of the 1930s are still serving along the boulevards as well.

West off the rue Royale runs the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, which, in addition to the British Embassy and the Elysée Palace (residence of the French president), has on its shop windows some of the prestigious names in Paris retail trade and has as its windows shoppers some of the most richly dressed and, at times, most beautiful women in the world.

Along the first 2,500 feet (800 metres) of the Champs-Elysées, between Concorde and the Rond-Point des Champs-Elysées, little has changed since the childhood of Marcel Proust. The 230-foot-wide avenue is bordered with chestnut trees, behind which on both sides are gardens, usually full of children, often with their nannies. Rides on donkeyback and in goat-drawn carts are still offered. Punch still punches Judy. The discreet pavilions in the gardens are tearooms, restaurants, and theatres. Along the paths it is still possible to get ones shoes dusty on the way to the office.

From the Rond Point up to the Arch of Triumph just about

everything has changed, and continues to change, along the

Champs-Elysées. Under the Second Empire this was a street of

luxurious town houses. Then came the Cafés, night-clubs, luxury

shops, and the cinemas, but the street retained its feeling of

luxury and the tree-shaded sidewalks (wide as a normal street)

offered promenades that were the pride of Paris. Since the 1950s,

however, more buildings designated as corporate headquarters

have evicted shops, tearooms, and hairdressers alike.

From the Rond Point up to the Arch of Triumph just about

everything has changed, and continues to change, along the

Champs-Elysées. Under the Second Empire this was a street of

luxurious town houses. Then came the Cafés, night-clubs, luxury

shops, and the cinemas, but the street retained its feeling of

luxury and the tree-shaded sidewalks (wide as a normal street)

offered promenades that were the pride of Paris. Since the 1950s,

however, more buildings designated as corporate headquarters

have evicted shops, tearooms, and hairdressers alike.

At the top of the Champs-Elysées is a circle 450 feet in diameter

from which 12 imposing avenues radiate to from a star (étoile).

From 1753 to 1970 it was called Place de l'Etoile, then was

renamed Place Charles de Gaulle. In the center of the circle is the

Arch of Triumph, commissioned by Napoleon in 1806. After

Napoleons fall it stood unfinished until Louis-Philippe saw to its

completion in 1832-36. At 50 metres, it is twice as high as the

Arch of Constantine, which inspired it, and, at 45 metres, a little

more than twice as wide. Jean Chalgrin was the architect and

François Rude sculpted the frieze and the spirited group. La

Marseilleise (real title, The departure of 1792). On Armistice

Day in 1920, the Unknown Soldier was buried under the centre

of the arch, and each evening the flame of remembrance is

rekindled by a different patriotic group.

At the top of the Champs-Elysées is a circle 450 feet in diameter

from which 12 imposing avenues radiate to from a star (étoile).

From 1753 to 1970 it was called Place de l'Etoile, then was

renamed Place Charles de Gaulle. In the center of the circle is the

Arch of Triumph, commissioned by Napoleon in 1806. After

Napoleons fall it stood unfinished until Louis-Philippe saw to its

completion in 1832-36. At 50 metres, it is twice as high as the

Arch of Constantine, which inspired it, and, at 45 metres, a little

more than twice as wide. Jean Chalgrin was the architect and

François Rude sculpted the frieze and the spirited group. La

Marseilleise (real title, The departure of 1792). On Armistice

Day in 1920, the Unknown Soldier was buried under the centre

of the arch, and each evening the flame of remembrance is

rekindled by a different patriotic group.

The westward thrust of the city was dramatically demonstrated in

the 1970s when the biggest concentration of tall buildings in the

nation arose over two miles beyond the Arch, on the far side of

the rich little suburban wedge of Neuilly. The site, called Quartier

de la Défense, was formerly just a place in the road where the

depressed suburban municipalities of Puteaux, Courbevoie, and

Nanterre listlessly touched. Now, 30 office towers, 30 stories

tall, heated and air conditioned from a central plant, are the hub

of a complex, balanced city plan.

The westward thrust of the city was dramatically demonstrated in

the 1970s when the biggest concentration of tall buildings in the

nation arose over two miles beyond the Arch, on the far side of

the rich little suburban wedge of Neuilly. The site, called Quartier

de la Défense, was formerly just a place in the road where the

depressed suburban municipalities of Puteaux, Courbevoie, and

Nanterre listlessly touched. Now, 30 office towers, 30 stories

tall, heated and air conditioned from a central plant, are the hub

of a complex, balanced city plan.

The ground level between the

buildings is a raised platform reserved to pedestrians, with roads

and parking below, shops, restaurants, cafés, a shopping centre,

hotels and apartment houses. Before the project was begun, the

state had already constructed at La Défense its Centre National

des Industries et des Techniques, an exhibition hall with 90,000

square metres of floor space. Nanterre became the site of a

campus of the University of Paris in the 1960s, and in the 1970s

specialized schools of university level were installed in the new

centre: a National School of Architecture, the National School of

Decorative Arts, the National Conservatory of Music, and the

Institute of Advanced Cinematographic Studies.

The ground level between the

buildings is a raised platform reserved to pedestrians, with roads

and parking below, shops, restaurants, cafés, a shopping centre,

hotels and apartment houses. Before the project was begun, the

state had already constructed at La Défense its Centre National

des Industries et des Techniques, an exhibition hall with 90,000

square metres of floor space. Nanterre became the site of a

campus of the University of Paris in the 1960s, and in the 1970s

specialized schools of university level were installed in the new

centre: a National School of Architecture, the National School of

Decorative Arts, the National Conservatory of Music, and the

Institute of Advanced Cinematographic Studies.